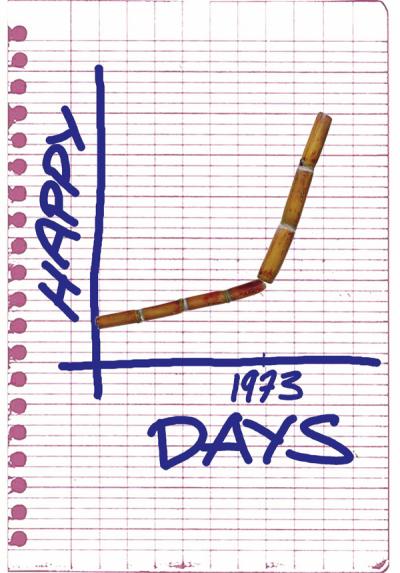

A lot has been recently said of the new economic miracle that is being sought by the new government coming to power in December 2014. Prime Minister Sir Anerood Jugnauth believes that there is an opportunity to create a new ‘economic miracle’ which he considers to be the second one after the first that occurred, according to him, in the mid-1980s. Although, this perception is reasonable, history evidences that there have been economic booms in the past but the first economic boom of post-colonial Mauritius took place in 1973 and lasted one year. This research article relates how the economic boom was created and why it should be considered as the first economic miracle.

Tough times of post-independence

After gaining independence in 1968, Mauritius was in a difficult situation like many other nations in Africa, Caribbean or the Pacific (ACP) that were also colonies of Great Britain. Shedding off administrative and financial ties with a former colonist was tough with contrasting perceptions of Mauritians. There was large immigration to Australia and those supporting independence found it a major challenge. Tensions in social relations led to racial disputes in the country during 1967-68 followed by the major strike in the sugar and port sectors in 1971 where industrial relations were clearly at stake. This was also accompanied by press censorship between 1971 and 1973 including the voting of the Industrial Relations Act (1973) which aimed to regulate industrial relations by making strikes known as illegal ‘grèves sauvages’. Clearly, that phase of the Mauritian economy was critical for the future of the economy. Nobel writer, V.S. Naipaul, during his visit to Mauritius, criticised the island as the ‘overcrowded barracoon’. The future then looked dim.

The ‘petrol shock’ of 1973 and the sugar boom

The Guardian (2011) points out that the 1970s oil crisis knocked the wind out of the global economy and helped trigger a stock market crash, soaring inflation and high unemployment. The most significant started in 1973 when Arab oil producers imposed an embargo. The decision to boycott America and punish the West in response to support for Israel in the Yom Kippur war against Egypt led the price of crude oil rise from $3 per barrel to $12 by 1974. The price of petrol rocketed, making all transport more expensive. Peretz et al (2001) explain that although the situation was not bright politically and financially between 1972 and 1975, the price of sugar started rising from $40 to $330 a tonne. The Mauritian quota under the European Economic Community Sugar Protocol-former EU-increased from 380 000 tonnes to 505 000 tonnes at a guaranteed price of £260 per tonne from the previous price of $57 per tonne. By 1974, sugar exports had risen to Rs 1584.2 million more than five-fold from 1971. In this way, the sugar boom cushioned the petrol shock and created the belief that Mauritius was on the path to recovery after being guaranteed a fixed price for sugar exports by the EEC in 1973 followed by similar agreement under the Lomé Convention in Togo in 1976.

OUTCOMES OF THE ECONOMIC BOOM

Consolidation of the Welfare State

To develop strong belief and acceptance of the elected government under the Labour Party-PMSD coalition, former Prime Minister, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam promoted the concept of ‘welfare state’, an important concept of Fabian School that Nobel Prize Winner, Amartya Sen reviewed as ‘welfare economics’ for India decades later. The Welfare State forwarded policies like universal pension, free health care, social security provisions, subsidies on staple food, etc. particularly for the vulnerable groups. The following are certain vivid examples. The SSR National Hospital was developed as a modern public hospital after the former Civil Hospital that accommodated patients from all over Mauritius. Road infrastructure was improved with more connections to remote small villages that were so far known as ‘habitations’ or ‘camps sucriers’. Electricity supply was extended to both municipal conurbations and villages including street lighting that was perceived as a luxury at that time. Subsidies were consistently maintained on staple foods like rice and flour.

COLA-The Cost of Living Allowance

A key development that took place during the 1973 sugar boom was the provision of compensation in a universal way – a first initiative after independence. Peretz et al. (2001) state that substantial wage increases, as well as end-of-year bonuses ranging from 1 to 22 months were granted to compensate the workers for the austerity endured since 1968. In Mauritius, common people spoke of COLA, a close term to Coca-Cola drink, which apparently meant higher earnings during the sugar boom and the possibility of greater spending from the working class. In November and December 1973, legislation by way of Wages Orders was passed in relation to Agricultural and Non-Agricultural workers of the Sugar Industry as well as in relation to workers of the Construction Industry which consecrated the principle of a Cost of Living Allowance becoming payable whenever the cost of living rose (CSAT, 1973).

The boom effect on the common citizen

The sugar boom effect was initially highly beneficial to the sugar industry which had 21 sugar factories in operation at that time. Since the average economic growth was on average 5.6% during the 1970s, agriculture was the core sector of the Mauritian economy. Although the sugar boom clearly spells out a first ‘miracle’ for Mauritius, little has been said of how it influenced the common citizen. At a time when the average earnings per inhabitant were some Rs 1,500, labourers could earn up to Rs 400 per month, teachers in schools up to Rs 700 and top earners or executives earned less than Rs 10 000. Better earnings and the COLA claimed greater need for better living. Iron-sheeted houses were partly renovated with concrete base and walls and the first ‘lakaz beton’, cosier and more spacious than ‘Longtill houses’ – which were subsidised for survivors of Carol Cyclone (1960) – appeared in villages and towns. At that time the Longtill Company was awarded the contract for the construction of the small houses (Vintage Mauritius, 2014).

Additionally, black and white television sets of ‘Sanyo’, ‘Sierra’, ‘Pye’ or ‘Bush’ brands were more privately owned by people at a time when watching TV in public was still common at social welfare centres. Greater consumption of commodities took place with the entry of certain luxuries like frozen meat – ‘boneless’ – and soft drinks, the one-litre version of Pepsi and Coca-Cola at Re 1. or little less became family drinks.

Secondary education was mainly privatised through lots of private colleges and only four State colleges namely QEC, RCC, RCPL and John Kennedy College. The University of Mauritius offered diploma courses in limited areas like sugar technology and agriculture. The 1973 sugar boom incidentally initiated the first movement of students to Indian universities in Chandigarh, Pune by 1975 with studies fully paid by meticulous private savings of the family.

The short-lived prosperity

From the internal economic side, Cyclone Gervaise with devastating winds of 280 km per hour destroyed most sugar plantations in early 1975 followed by a long period of electrical blackout, food rationing, makeshift primary and secondary schools and dire austerity. Unemployment rose again in a fragile economy and the term ‘chômeur’ literally meant the return of bad days. In a time of despair, the population secretly developed resilience after the unexpected sugar boom of 1973 which nevertheless once gleamed like a flash of a fry pan in times of turbulence.

Conclusion

The first economic boom of Mauritius is typical of times of hope for developing economies where there is a general feeling that the country is moving to an elevated standard of living with benefits and opportunities that will be reaped by all people. Economic cycles are not permanent or enduring, they will have to cease at a particular time. Yeung Lam Ko (1998) states that Mauritius, like other countries which had just shaken off their shackles of colonisation, did have to face the various problems of an underdeveloped or a poor economy. These were mainly a low level of gross domestic or national output coupled with a low level of savings, a relatively low level of technological know-how and a relatively low level of management and technical skills generated through the educational sector which was too academically biased. These factors compounded to the aftermath of the economic boom which was more a causal factor than a planned success strategy. A similar economic boom was followed during the mid-1980s in Mauritius and its sequels are still being borne by Mauritians especially when unemployment is now common feature in the economy and means to solve them since the boom periods remain difficult.

King Sugar, the first economic boom of 1973

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻

- Publicité -