On 1st February 2012, the Government of Mauritius and the Mauritian nation will be commemorating the 177th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Mauritius. It is a day when the terrible plight of the Mauritian slaves, their struggle for freedom and the importance of freedom in the shaping of Mauritian history is remembered and honored. Until recently, slavery and acts of slave resistance such as slave conspiracies, slave revolts, maroonage (or the practice of slaves running away from their masters) and maroon attacks during the Dutch East India Company’s administration of Mauritius have been largely unexplored themes in modern Mauritian slave historiography.

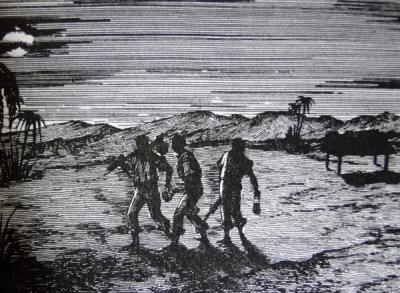

The First Freedom Fighters on Mauritian Soil

The climax of slave resistance in T’Eylandt Mauritius or Dutch Mauritius took place on the morning of 18th June, 1695, when Aaron of Amboina, Antoni alias Bamboes, Anna of Bengal, Paul, a recently arrived slave from Batavia, and Esperance, a female slave belonging to the free burgher, Class van Wieringen, set fire to Fort Fredrick Hendrik, after weeks of minute preparation.

Everything went up in smoke and Governor Deodati barely saved himself in his shirt. Soon after, in order to underline the seriousness of this situation, he wrote to the Dutch governor of the Cape Colony (located formerly in the present-day Western Province of South Africa) that: “These were matters of very dangerous consequences, tending to the utter ruin of this island.”

In their confessions, after their capture, the slave rebels clearly acknowledged that they had planned several weeks prior to destroy the fort and that their chief objective was to burn the governor and all the Company’s employees and servants. Immediately after, they planned to put the houses of the free burghers to the torch in order to become the masters of the island and bring an end to Dutch rule.

For Deodati, the VOC employees, and the free burghers, this was a nightmare scenario come true. But, at the same time, it was evident that “these first freedom fighters on Mauritian soil” had sounded the clarion call of liberty. The slave rebels were sentenced to death and Governor Deodati ordered his men to carry out the execution order without waiting for instruction from Governor Simon van der Stel from the Cape Colony his superior colonial officer (It is interesting to note that Simon Van der Stel was born in Mauritius in 1640 and he was the son of Adrian Van der Stel).

More than seventy years ago, Herbert Aptheker, an American slave historian, explained that: “A Ruling class, often subjected to periods of panic arising from doubt of its ability to maintain its power, may be expected to develop very complex and thorough systems of control”.

As a result, during periods of social crisis, a ruling class in a slave society developed “numerous psychological, social, juridicial, economic, and militaristic methods of suppression and oppression”.

Aptheker’s observations can also be applied to Dutch Mauritius during the 1690s. After all, during the weeks and months immediately following the burning of the Dutch fort, there was a brief period of crisis and panic on the island and in the eyes of the colonial officials and colonists, “desperate times called for desparate measures”. Therefore, the punishment which the Dutch inflicted on these rebel slaves was of the utmost barbarity. In the process, the objective was for it to serve as a powerful example in order to prevent the other slaves and maroons from attacking the other Dutch settlements as well as openly challenging Dutch colonial authority in Mauritius.

However, even the most inhumane punishment of the VOC officials could not deter the comrades of the first Mauritian freedom fighters, who were still hiding in the woods, from continuing their struggle. After 1695, Fort Frederick Hendryk was rebuilt in stone like the Castle Good Hope in Cape Town. As a result, the slave rebels and maroons were able to influence the architecture of the most important building in T’Eylandt Mauritius. During the late 1690s and early 1700s, there a few other maroon attacks and slave conspiracies which was one of the major reasons which convinced the Dutch to permanently abandon Mauritius.

It does not take much to realize that on each of 1st February, the struggle for freedom of the slaves and maroons during the Dutch period between 1638 and 1710 should be remembered and honored. This is the most meaningful way that we, the citizens of the Republic of Mauritius, can commemorate the making of our unique and rich history as a people.

“THE LONG STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM”: Slavery and Resistance in Dutch Mauritius, c.1638-1710

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻