Introduction

From time immemorial, famous cases of miscarriages of injustice in the history of mankind such as Trial of Socrates, Jesus Christ’s Crucifixion, the Galileo Affair, Copernicus’s Persecution, HYPERLINK « https://www.facebook.com/pages/Joan-of-Arc/112715575408261 » \o « Joan of Arc »Joan of Arc, and HYPERLINK « https://www.facebook.com/pages/Dreyfus-affair/109793755714244 » \o « Dreyfus affair »Dreyfus Affair have undeniably retained our utmost attention. Even nowadays, whenever there are debates and researches about the very topic ‘Miscarriages of Justice’, such cases are still assuming great relevance and newsworthiness. With the advent of the Magna Carta matters regarding justice started to evolve significantly and positively. The principle of the British Legal System (as per Human Rights Review 2012) regarding fair trial that ‘people will be fairly heard and judged in court’, is in fact enshrined prominently in the clause 40 of the 1215 Magna Carta which is “To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice”.

Definition

According to Walker and Stamer (1999), “a ‘miscarriage’ means literally a failure to reach an intended destination or goal. A miscarriage of justice is therefore, mutatis mutandis, a failure to attain the desired end result of ‘justice’…[and] the meaning is not confined to miscarriages in court or in the penal system [only, but they may also] arise on the street when the police unjustly exercise their coercive powers”. Corresponding to this very definition, it is meaningful to pay attention to the words of Lord Justice Schiemann in his judgement (on the Merits of Mullen’s appeal) in Naughton (2007), about the position of the criminal justice system and miscarriages of justice as follows:

The phrase ‘miscarriage of justice’ does not simply mean that a guilty man has escaped, or that an innocent man has been convicted. It is equally applicable to cases where the acquittal or the conviction has resulted from some form of trial in which the essential rights of the people or the defendant were disregarded or denied (R (Mullen) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2002] EWCA Civ 1882).

Causes of Wrongful Convictions

In connection with miscarriages of justice, Gould and Leo (2010), have identified the following sources of wrongful convictions such as: “(1) mistaken eyewitness identification (2) false confessions (3) tunnel vision (4) informant testimony (5) imperfect forensic science (6) prosecutorial misconduct (7) inadequate defence representation (8) interrelated themes such as questions of race, inadequate post-conviction remedies and the role of the media [and other issues in pari materia as police misconduct, creed discrimination, religious fundamentalism, judicial corruption, political wrangling, and ‘over-zealous police investigation’] ”. Specifically amongst all these issues, we will discuss about ‘false confessions’ for the purpose of this paper since they are ‘among the leading causes of wrongful convictions’ (as per FalseConfessions.Org – Facts & Figures). Moreover, they are correspondingly the subject of much discussion, debate and research in our modern society.

False Confessions

As to whether ‘confessions’ from the police are trustworthy or not, is indeed problematic as far as the criminal justice system and modern jurisdictions are concerned. Solutions to this problem are apparently very difficult as a number of other complex problems are intertwined together. For instance, when an innocent person is just about to be arrested and handcuffed by the police, a so called stereotyping as ‘guilty’ takes place whether one is innocent or not. Even in the developed countries this anomalous scenario is manifesting itself irrationally. Although such an arrest is lawful, it is entirely primitive and savage. It leaves much to be desired, since the suspect is appallingly tagged as a ‘repugnant criminal’. Instead of treating the ‘suspect’ as ‘innocent until proven guilty’, the police take actions according to the ‘guilty until proven innocent’ belief, which is highly objectionable. This so called flawed behaviour of the police in general is to be condemned severely, for the simple reason that it shamefully causes the blatant perversion of the course of justice. As a consequence, the constitutional rights of the suspect are desecrated. In addition to this, police brutality and extorted confessions are triggering important discussions because unlawful and unethical methodologies are being adopted by the police to acquire ‘false confessions’. These perturbations have been analysed clearly and thoroughly by Gould and Leo (2010). On the one hand, the latter affirm that in high profile cases the police is under great pressure to solve the crime. On the other hand, they also state that there is the unlawful use of psychologically coercive police interrogation methods. For instance, ‘third degree’ methods are used in parallel with incommunicado interrogations. Such ‘traumatic and nasty’ tactics do violate the principles of law, natural justice, ethics, fairness, fair play, democratic rights, constitutional rights and human rights to the extreme. In the light of what has been said, the confessions and investigations from the police are not immune from foul-plays and malpractices. As such they might not be infallible and their credibility could be challenged on various thresholds since they could have been acquired in obscure circumstances (other than incommunicado detention). Furthermore, it is also well known that in certain countries, police officers do exhibit over-zealousness (which is fundamentally unethical) while carrying out their investigations in order to acquire confessions from the suspect. In Langdon and Wilson (2005, p.8), a study in Australia and New Zealand found that over-zealousness from the police was a major contributing factor leading to miscarriages of justice.

Bombing Cases

If we analyze certain cases relating to miscarriages of justice, we will find strong similarities and co-incidences. For instance, the careful examination of cases such as the Guildford Four, Birmingham Six, Maguire Seven and Judith Ward do reveal interesting facts to us. According to Macfarlane (2005) regarding these bombing cases, the first analysis is that state authorities could convict an innocent despite of contradictory evidence because of adverse public opinion. Second, scientists working in such cases could prefer to work in close collaboration with the police and prosecution rather than to provide impartial and [independent] analysis. Third, scientists could disclose to the prosecution evidence of any tests that although was not requested for any such disclosure. Fourth, we could ourselves apparently note with astonishment that certain Governments, authorities, communities and legal bodies very often would not wish to see the police being undermined, dented and blotted even if the latter was bias, ruthless, corrupt, over-zealous, unethical, unlawful and incompetent to the very core.

Innocence versus Legal Technicality

Regarding the ‘innocence’ matter, doubts do arise when and where there is a legal technicality. Joshua Marquis as cited in Zalman (2011) has decried the improper usage of ‘innocence’ when describing defendants who are released from prison on what some might consider a ‘legal technicality’. Conversely, pertaining to this question of innocence versus legal technicality, Walker and Stamer (1999) argue constructively that even a criminal who has committed a crime could be said to have suffered a miscarriage of justice if convicted by legal procedures that violated the former’s basic rights. Thus, in agreement with this pertinent volte face, castigating even a criminal who has been liberated on technicality grounds would be legally unfair.

Rectification

DNA exonerations have made a commanding impression in the sphere of criminal justice by quashing a number of cases relating to miscarriages of justice. But yet, other developments need to be carried out if we want to rectify miscarriages of justice completely and restore confidence in the rule of law and justice. Likewise, Kyle (2004) advises that a reform that will rectify miscarriages of justice has to take place from the beginning of a police investigation through the point when the suspects have exhausted their rights of appeal. This measure is in fact ‘mentioned by the British Government to the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice’. For Gould and Leo (2010,) an Innocence Commission could be set up where judges, attorneys, lawyers, police officers, engineers, professors , scientists and forensic doctors could team up together and provide a ‘blue ribbon panel’ that would tackle miscarriages of justice at all echelons. In parallel with this, reforms starting from the police station to the office of the Commissioner of Police should be prompted. No change and improvements can take place, unless such reforms are carried out in depth. Another problem to be tackled at any cost is that of delay with regard to due process of law. If we want a sacred paradigm of justice in our modern society, then the essential principles of modern jurisdictions based upon the famous maxim “Justice delayed is justice denied” will have to be juxtaposed with those of the quote 40 of the 1215 Magna Carta.

Conclusion

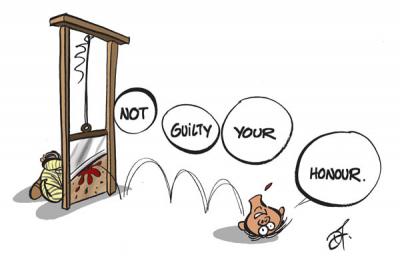

To sum up, it would be judicious to rely on Lord Denning’s comment (in response to the Guildford Four case) that “even if the wrong people were convicted, the whole community would be satisfied”. Pertaining to this issue of wrongful conviction vis-à-vis the community, matters are worsened when some very dangerous people in the legal arena prefer to act ‘En Ame et Conscience’ as far as the accountability of their actions and reactions is concerned, rather than as per the ‘Rule of Law’. This entails serious repercussions since the guilty is exculpated from blame at the expense of the innocent and other scapegoats who are sadly guillotined on the legal scaffold. To counteract such an unethical and unlawful impetus, it is imperative to have recourse to other legal techniques of scrutiny and investigation to prevent the constitutional rights of the innocent from being jeopardized. We need to re-think and reframe our fact-finding strategies. For instance, a technique known as the ‘Path Analysis’ could be adopted by the judicial system. As elaborated by Gould and Leo (2010), this would permit ‘tracing a case through investigation and prosecution’. This would be similar to a decision tree method that would finally culminate into a factual synopsis that would allow us within the periphery of justice to start ‘discussing outside the box critically’ rather than ‘narrating inside the box descriptively.

References

Article 6: The right to a fair trial, Human Rights Review 2012

Crime, Power and Marginalisation: Miscarriage of Justice Cases in Australia and New Zealand, Presented to the Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology Conference, Auckland, New Zealand 27 to 29 November 2012

FalseConfessions.Org, Facts & Figures, HYPERLINK « http://www.falseconfessions.org/fact-a-figures »http://www.falseconfessions.org/fact-a-figures

GOULD JON B & A. LEO RICHARD, II. JUSTICE IN ACTION – ONE HUNDRED YEARS LATER: WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS AFTER A CENTURY OF RESEARCH, THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINILOGY, Vol. 100, NO. 3, 2010

Kyle David, CORRECTING MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE: THE ROLE OF THE CRIMINAL CASES REVIEW COMMISSION, Drake Law Review, Vol. 52, 2004

Macfarlane Bruce, Convicting the Innocent: A Triple Failure of the Justice System, MANITOBA LAW JOURNAL VOL 31NO 3 (2005)

Naughton Michael, Re-Thinking Miscarriages of Justice: Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg, London:Palgrave Macmillan, 2007

RUTBERG SUSAN, ANATOMY OF A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE: THE WRONGFUL CONVICTION OF PETER J.ROSE, GOLDEN GATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW, Vol. 37, 2006

Walker Clive and Starmer Keir, Miscarriages of Justice: A Review of Justice in Error, Chapter 2, 1999

Zalman Marvin, AN INTEGRATED JUSTICE MODEL OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS, Vol. 74.3, 2011

Miscarriages of Justice

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻