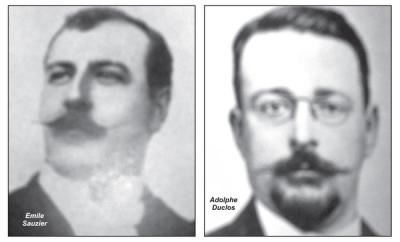

Rodrigues was much in the limelight even more than a century ago. Though constitutionally, the island had no nominated or elected representatives sitting in the Mauritius Legislative Council and that was to be so until 1967, a number of Mauritian politicians sensible to the cause of the inhabitants of Rodrigues would not hesitate to take up the cudgels in their favour. The motion that was tabled in the Council by the member for Pamplemousses, Emile Sauzier, on 19 November 1901 alerted the Council about the « unlawful and arbitrary acts » that were being perpetrated by the Magistrate, Edward McMillan, posted in Rodrigues.

Urging the Governor of Mauritius, Sir Charles Bruce, to set up a Commission to probe into the alleged abuses for which Magistrate McMillan was accused of, Emile Sauzier set two questions that read thus :

(i) « Is the Government aware that constable Collard Perinne by order of the magistrate of Rodrigues flogged a boy by the name of Ange Roussety in a public place for alleged attacks on the magistrate’s character ? »

(ii) Is the Government aware that the magistrate of Rodrigues inflicts in cases of larceny both imprisonment and fine ? »

The Governor lost no time instructing the Colonial Secretary to wire Sauzier’s queries to Magistrate McMillan to seek clarifications on the charges levelled against him.

The Magistrate responded on 20 November. He wrote : « First question is in the affirmative. Boy Roussety placarded most obscure pamphlet against my character. After police inquiry proving guilt, mother was sent for who prayed that son be not imprisoned. She therefore consented to boy being flogged with rattan as she could not do so herself on account of boy’s violent temper ».

« The second question is also in the affirmative. After repeated convictions of larceny and possession of stolen property, three men convicted for larceny and sentenced to maximum fine and imprisonment in virtue of Ordinance 6 of 1866 and 31 of 1882… »

Acting on the advice of the Procureur-General to the effect that the Magistrate had misinterpreted Ordinance 6 of 1866, Sir Charles Bruce cabled McMillan informing him that the simultaneous imposition of fine and imprisonment for the one and same offence was illegal.

But it was wrong to think that the matter was going to end here. Barthélemy Roussety, the father of the 15year old boy, Ange Roussety, had already arrived in Mauritius. His aim was to alert the Mauritian public about McMillan’s overzealousness in going out of bounds and his abuse of authority. And so, got the support of two of our prominent members of the Legislative Council — Emile Sauzier and Adolphe Duclos.

Barthélemy Roussety belonged to a well-known family in Rodrigues. But he was also known to be a rabble-rouser, stirring troubles in Port Mathurin since 1898. With his followers, he staged street protests, as for example, in 1902, he led a protest march against Magistrate Rouillard, the highest authority in Rodrigues, whose administration, he said, « laisse beaucoup à désirer….et ses jugements sont tout-à-fait bizarres ». So much so that the frenzy of excitement often displayed by Roussety’s follower was feared to go out of control. In 1902, the tense atmosphere forced the authorities in Mauritius to despatch in all haste a police reinforcement of 20 armed men led by a « European Inspector » to ensure that public peace was not disturbed in the dependency.

Nonetheless, Governor Bruce seriously took into account Sauzier’s demand for a Commission of Inquiry as he too seemed far from being satisfied with the explanations furnished by the Magistrate. But more than that his intention was to defuse the social tension that was brewing in Rodrigues.

Mcmillan, a « complete failure »

The three Commissioners appointed to conduct the investigations, Justice A. Wood Renton, Hon. A. Thibaud and District Magistrate S. H. Colin boarded the’Futala’bound for Colombo after the ship’s Captain in a good gesture having agreed to halt on the way at Rodrigues to drop the Commissioners so that they could begin their assignments in earnest.

Indeed, writing to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London a letter dated 25 January 1902, the Governor referred in it to the the Commissioners’report stating that in September 1901, Magistrate McMillan flew into a rage on seeing posters displayed on shops’walls mentioning he was having an »affair » with a young « Rodriguan » woman. A police investigation had revealed that the boy Ange Roussety had put up those posters encouraged by the boy’s uncle, one Edgar Calamel

Relying on the Commissioners’report, Sir Charles wrote that when the boy was about to be flogged, a large crowd gathered in front of the Police Station in Port Mathurin to watch the scene. The boy’s hands were held together with a rope and a policeman began inflicting strokes with a rattan. Another policeman counted viva voce each stroke being administered until he reached the 25th stroke.

The Commissioners wrote that public flogging though abolished was still carried out by the order of the Magistrate and in that case, it was on a boy under the age of 16. The Magistrate’s decision, they argued, was not a sound one. Furthermore, although the boy’s mother consented to flogging on his child, the number of strokes exceeded 18 contrary to Ordinance 17 of 1882 as much as the use of rattan was prohibited by the same Ordinance.

The Commissioners found out that McMillan « committed several serious errors » in the course of his duties.

« After careful consideration of the report, I am of opinion », Sir Charles wrote, « that it is in the public interest that McMillan should not continue to hold the appointment of Rodrigues but should be transferred to some other appointment in the public service… »

In the end, it transpired that Edward McMillan was not a lawyer, had no legal background nor any administrative experience and therefore one unsuitable for the highest position for which he was assigned in Rodrigues. Prior to his nomination as Magistrate, he was a petty clerk in the British Consulate at Tamatave. « He spoke English, French and the local patois with equal ease », wrote the Governor.

It also came out that McMillan’s appointment at the helm of the Rodrigues administration was backed by an official at the Colonial Office.

In a sharp barrage of criticism, Emile Sauzier laid the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Secretary of State and the Governor of Mauritius for that appointment stating that the end result proved that McMillan was « a complete failure ».

Mauritians championing the cause of Rodriguans

But McMillan despite being removed from Rodrigues continued to enjoy for obscure reasons the support of the Colonial office. His new appointment as Registrar in the Colonial secretary’s office in Port Louis drew the wrath of the member for Flacq, Adolphe Duclos, who tabled a motion on 2 July 1902 to the effect that since the charges against the former Magistrate of Rodrigues had been proved, he should answer for his scandalous behaviour.

Protesting against McMillan’s new appointment, Duclos claimed in the Council of Government that « l’intérêt public exige que vous traduisiez M. McMillan devant le Conseil Exécutif ; l’intérêt public m’ordonnait de prendre l’attitude que j’ai prise, afin que les habitants de Rodrigues sachent qu’il se trouve à ce Conseil des hommes prêts a les défendre contre ceux qui iraient chez eux rendre une justice tout autre que celle qu’íls ont pour devoir de rendre… »

The Procureur-General opposed Duclos’motion but in August 1902, Duclos shot another motion to the effect that « a compensation be offered to the aggrieved inhabitants of Rodrigues for the hardships and sufferings as a result of the maladministration of M. McMillan ». Such a compensation, said the member for Flacq, was to be seen as a « réparation eclatante » to the victims of « judicial injustice ». The motion was again defeated but the inhabitants of Rodrigues were assured that in the Council of Government in Mauritius in the 1900s, there were Mauritians like Emile Sauzier and Adolphe Duclos who were ready to listen to their grievances and champion their causes.

HISTORY : To Rodrigues, with love from Emile Sauzier and Adolphe Duclos (1901)

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻